Linux.com

Everything Linux and Open Source

Don't forget the text editor

Text

editors are important for many tasks, from editing configuration files,

nudging cron jobs, and manipulating XML files to quickly pushing out a

README. Luckily, there are a number of interesting editors available.

Here's a brief introduction to nine intriguing choices. While some may

be better suited to certain tasks, it's no one tool is better than

another for all tasks. Try them all and use the ones you like best.

vi

Old favorite vi (or one

of its variants, such as Vim or Elvis) is available on most *nix

systems. If you are a system administrator moving from one *nix system

to another, the one reliable fact is that vi will work, macros

and all. Once you have learned the keystrokes, swapping words at the

boundaries, replacing sections of text, or transversing through a large

file with vi is efficient, fast, and predictable. However, its initial

learning curve is somewhat steep, and there is no real GUI.

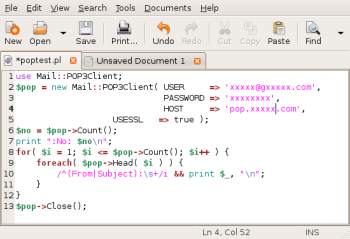

Gedit and Kate

Gedit (see figure 1) is a small and

lightweight text editor for the GNOME desktop, and the default text

editor for Ubuntu. An excellent tool with syntax highlighting for a

wealth of scripting and programming languages, it allows for extension

via plugins (figure 2) and does most tasks efficiently, without fuss.

The editor is modern in design, with a tab per open file, thus allowing

for easy cut and pasting between documents. The interface is

uncluttered and somewhat configurable via Edit -> Preferences for

such attributes as the enabling of allowing line numbering and changing

tabs to spaces.

You can also run Kate (KDE Advanced Text Editor) under the GNOME desktop. However, you will have to install its package with a command like sudo apt-get install kate-plugins, which will also install some extra plugin-enabled functionality. Kate has a slightly busier interface than Gedit (figure 3),

and to use tabbing between documents, you must activate the feature via

enabling the correct plugin. But Kate is significantly more

configurable than Gedit, exposing more of its innards as preferences.

An immediately helpful feature is the ability to hide code that is

within a certain scope. For example, to hide all the code within a

foreach statement, double-click on the offending line. This is a

significant help for uncluttering verbose scripting text. Also, under

the Tools menu, you can change the end of line type to switch between

Unix, DOS, and Mac, thus avoiding subtle issues in your text later.

Both Kate and Gedit support quick ad-hoc editing of numerous

scripting and programming languages. They are both excellent editors

for a variety of tasks.

TEA and Emacs

Emacs and TEA

are more complex and configurable than Gedit and Kate, with a much

wider scope of potential abilities. If you want to work within a single

environment, including sending mail, then these adaptive tools have the

power to let you.

TEA (figure 4)

is a compact, configurable, and function-rich editor that takes up only

around 500KB of memory. TEA provides a decent text editor, with markup

support for LaTeX, DocBook, Wikipedia, and HTML. It does not provide

any syntax highlighting, but does provide an extremely basic project

environment for compiling code.

Thankfully, TEA also contains a delightfully named crapbook (read

notes holder) for storing temporary text. The editor provides a spell

checker and statistics for documents and therefore sits comfortably

between an office suite and a plain editor. Other functionality

includes a file browser and a calendar. Because the editor's compact

size is based on the fact that it relies heavily on using external

tools, under the Help menu there is a well-thought-out self-check

command that on activation mentions any missing dependencies.

You can extend TEA via manipulating text files to expand specific

features. For example, to add your own command to the Run menu, open

the ext_programs text file via File -> Manage utility Files ->

External programs to add the option xterm, which activates -- yes, you

guessed it -- an xterm window. Add and save the text on a new line:

xterm=xterm &

Emacs (figure 5)

is powerful, feature-rich, and configurable. This tool has a long

history reaching back as far as 1976. Originally written by Richard

Stallman and Guy Steele, Emacs split into two main branches, Xemacs and

Emacs, in 1991. The functionality in both branches is comparable.

Having a long and renowned history implies fitness of purpose and core

stability.

Emacs is not only a text editor but also an interpreter for Emacs

Lisp, an extension of the Lisp programming language. Elisp makes

scripting relatively easy. If you are a power user, you can tweak the

.emacs configuration file (or whatever your local equivalent is) to,

for example, add extra menus.

People have written a large number of modes in the Elisp language

exist. A mode is an extension, modification, or enhancement. For

example, one mode may be for SQL development, and another for Perl

programming. The main Emacs wiki details the most up-to-date information and lists a full set of potential modes.

Emacs' default GUI is succinct and contains much functionality

beyond editing. You can perform file navigation, send out email (if

configured correctly), and perform specific tasks such as debugging,

patching, and creating diffs with a few succinct keystrokes.

The software's documentation and international language support is superb, and the editor includes an online tutorial.

Gaining full mastery of Emacs, even for the cleverest among us,

requires patience and time. The intuitive use of buffers or the

memorizing of Ctrl and Alt keystroke combinations is a chore, but if

you perfect it, expect massive gains in efficiency.

Leafpad, Mousepad, and Medit

If you are looking for a simple editor that does the bare minimum, then either Leafpad or Mousepad

will fulfill the basics. They look the same and allow for word wrap,

line numbering, auto indent, and a choice of fonts, and not much else.

Medit is a

straightforward text editor with syntax highlighting and tabbed panes.

To add an entry to its configurable tool menu (figure 6) select

Settings -> Preferences then highlight the Tools option. Clicking on

the new item icon (the picture of a document with the orange circle at

the bottom center) activates a dialog. Change the name of the item from

"new command," then add the entries displayed in figure 5. You will

then have a new tool that lists in the currently selected document all

the running processes (figure 7). For the devotees, Medit has its own

scripting language, called mooscript.

The editor also has a well placed expandable no fuss file selector

that is readily available via a click on the right side of the main

window.

SciTE

SciTE, the Scintilla-based

text editor, offers some of the features of a programmer's interactive

development environment. It supports tab panes, syntax highlighting,

and code folding, and goes a solid step further for programmers. For

example, on opening a Perl file, or numerous other languages, you can

check a script's basic validity via the menu option Tools -> Check

syntax. That displays a second window (figure 8) with the gruesome

details.

SciTE presents a no-fuss, easy-to-learn approach to controlling a scripting environment. A development tool like Eclipse will give you more features and adaptability, but also a steeper learning curve.

Final comments

This article covers only a fraction of the available text editors

for the Linux desktop. If I have missed your favorite, share your

opinion and place a link in the comments section for this article.

No comments:

Post a Comment